This post is part of Africa Lead’s Final Program Year Learning Series and has been published in advance of the upcoming August 7th, 2019 Learning Series Event – Leadership for Africa’s Food Security: The Hard Facts About the Soft Art of Facilitative Leadership. The author is Steve Smith, Africa Lead Chief of Party.

In today’s world, data is the weapon of choice. Businesses, governments and even NGOs are investing more in data collection and analysis, with the intention to use this information to inform strategies and decisions, and in many cases to defeat the competition.

Certainly data can be powerful, but its effect on strategies and decisions isn’t straight forward. For example, timely data collected by the private sector often does not even lead to decisions.

There is something just as important as data for decision making, especially in making decisions that affect multiple stakeholders. It’s not something new. It is something that has driven decision making for tens of thousands of years, and now it is making a comeback as a focus of attention and study by organizational development specialists, psychologists, executive coaches, and businesses everywhere.

This “something’ is human nature. No matter how good the data, there are always humans – with their emotions and insecurities – behind the decisions.

Multi-Stakeholder Solutions are Not Technical; they are Emotional

Decisions are not made among multi-stakeholders based primarily on science and data, rather based on peoples’ emotions, fears and interactions.

According to Chris Ansell and Alison Gash in their paper Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice, the more that stakeholders fundamentally distrust each other, the more leadership must assume the role of honest broker. Picture this multi-stakeholder scenario:

A group of organizations from the private sector, government and civil society are brought together to agree on a new seed policy. The basic interests of these organizations are in conflict with one another. The representatives assigned to the group have never worked constructively together and likely harbor mistrust for one another. No single organization has positional authority: the government ultimately has the power to make the policy, but it doesn’t have the authority to tell others in the group what to think or do.

In this scenario, it is highly unlikely that any consensus-based solution could be achieved by anchoring the multi-stakeholder mediations in data sets. The better path to a mutually beneficial solution is through emotionally intelligent leadership, or “facilitative leadership”. This is what thousands of years of historical accounts of leaders and nations struggling for have told us. And if history weren’t convincing enough, now we have neuroscience to explain it.

When people interact, our inner and more primitive brain – the limbic system – dominates our more modern brain – the pre-frontal lobe. Our emotions reside in the limbic system, whereas our cognitive abilities are found in the pre-frontal lobe. This is why a group of diverse stakeholders in the same room are more likely to be moved by fear and a sense of survival than by facts. In these situations, our instinct is to protect ourselves by putting up defenses, withholding information and attacking others. This can result in a “winner takes all” scenario, leaving others in the group with nothing to show for their effort, or worse, to go down in defeat.

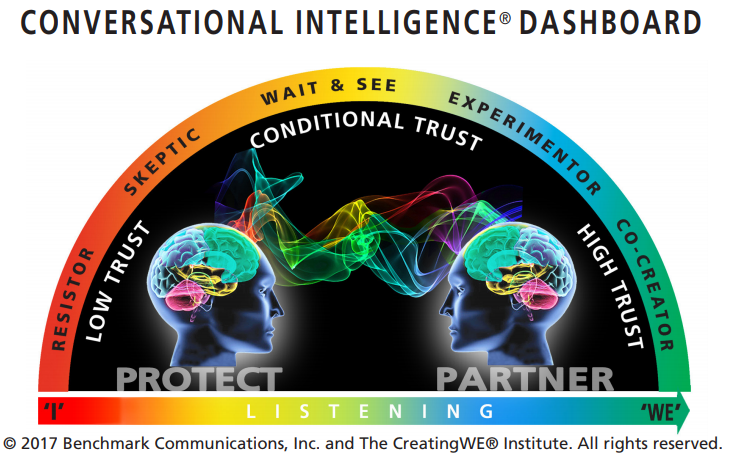

Fortunately, this is not the inevitable outcome. Neuroscience shows how effective leaders can be sensitive to the primitive brains of the group members, effectively converting them to partners. Through conversational intelligence, a tool of emotionally intelligent leaders, one can help create the conditions for the co-creation of mutually beneficial solutions.

This process is diagrammed above in the “Conversational Intelligence Dashboard,” developed by Judith Glaser and Ross Tartel, to show the emotional responses to contrasting approaches to leadership.

The facilitative leader focuses on relationships by first giving members of the group opportunities to share their needs and aspirations. This begins to make people feel safe, the first step in building trust. Listening, as opposed to telling, leads to connections among group members. The brains of group members receive signals of trust and makes them open to influence. The result is the ability to co-create and build shared success.

Facilitative Leadership Takes Time to Develop and is Hard to Measure

Technical skills – the hard skills – are at a premium in the development business. They build the engines that drive change. But those engines can’t function without emotional intelligence skills – the soft skills that lubricate those engines, especially in complex multi-stakeholder processes where no single organization has positional authority over the rest. Taking this a step further, it is the emotional skills found in facilitative leadership that enable technical skills and technical solutions to thrive. Multi-stakeholder solutions begin and end with facilitative leadership, not with technical skills.

Referring back to conversational intelligence, moving towards “we” starts with the emotional skills of the leader, who must be especially self-aware and socially aware. Unfortunately, there is no quick and easy formula to measure the development of these skills. Whereas technical skills can be learned, memorized and applied, emotional skills are mainly learned in the limbic system. This is where emotions and behaviors are hard-wired into habits. Changing these habits takes commitment to continuous learning and practice. It is hard work.

One reason organizations under-appreciate and under-emphasize emotional skills is because they don’t lend themselves to measurement. Cognitive skills and the outputs from using them can be quantified, as in the design of a durable, cost-saving water system. The emotional intelligence skills of a deft facilitative leader, on the other hand, elude our measurement. There are no counter-factual evaluation models to assess the facilitative leader.

There are, however, a growing number of studies that clearly quantify the superior performance of organizations led by emotionally intelligent leaders. This information should be enough to rethink how we select key managers and how much we invest in their emotional leadership skills development. It has been enough for the private sector, which according to a recent study conducted by the Center for Creative Leadership, companies that rated “highly for their investments in human capital deliver stock market returns 5 times higher than those of companies with less emphasis on human capital.” Further, in his book Working with Emotional Intelligence psychologist and award-winning author Daniel Goleman wrote, “in a study of skills that distinguish star performers in every field from entry-level jobs to executive positions, the single most important factor was not IQ, advanced degrees, or technical experience, it was EQ (emotional quotient). Of the competencies required for excellence in performance in the job studies, 67 percent were emotional competencies.”

Facilitative Leadership for All

Let’s finish with a few final thoughts on facilitative leadership of multi-stakeholder processes. Just as with any single organization, these leaders aren’t effective because of their title or because they are appointed or because they rotate into the role. More often than not, as Ansell and Gash state, facilitative leaders emerge organically from within the community of stakeholders. This is one of the best things about facilitative leadership: nearly anyone can do it because it is not confined to the person with the title.

Facilitative leaders are fundamental to building sustainable structures and processes. Unlike technical skills, which need to be recruited and updated for each and every specialized topic, facilitative leadership is a skill that can be applied broadly across topics. Once institutions prioritize facilitative leadership and develop facilitative leaders, the investment will be sustained well into the future.

That said, facilitative leaders don’t just sprout out of any organization. Facilitative leaders come from organizations with emotionally intelligent cultures characterized by empathy, trust, open communication and teamwork. Any organization that seeks to practice facilitative leadership in multi-stakeholder settings must model emotional intelligence at home. And if what I said up front in this blog about multi-stakeholder processes being a fundamental part of any development organization is true, we all need to look hard at our own organizational cultures as a first order of business.

Keep Learning about Facilitative Leadership with Africa Lead

In the coming weeks, we’ll be exploring facilitative leadership and Africa Lead’s programming to strengthen human capital for food security across the continent, as part of Africa Lead’s Final Program Year Learning Series.

Join us on August 7th, 2019 for the event Leadership for Africa’s Food Security: The Hard Facts About the Soft Art of Facilitative Leadership

The event will be held in conjunction with Africa Lead and the African Management Initiatives’s final day programming of the East and Southern Africa six-month Executive Leadership Course for Africa’s Food Security.

The learning event will bring together development practitioners and managers working in food security, agricultural development, resilience building and governance to engage in a compelling conversation about facilitative leadership.

Register for the in-person event