This report is structured in an easy-to-navigate format. It will help you learn about Africa Lead’s origins as a program, how it supported Africa’s food security policy developments from the boardroom to the farm, helped leaders and institutions across the continent advance toward achieving their shared goals, and how the program’s unique approaches were designed through continual learning and adapting.

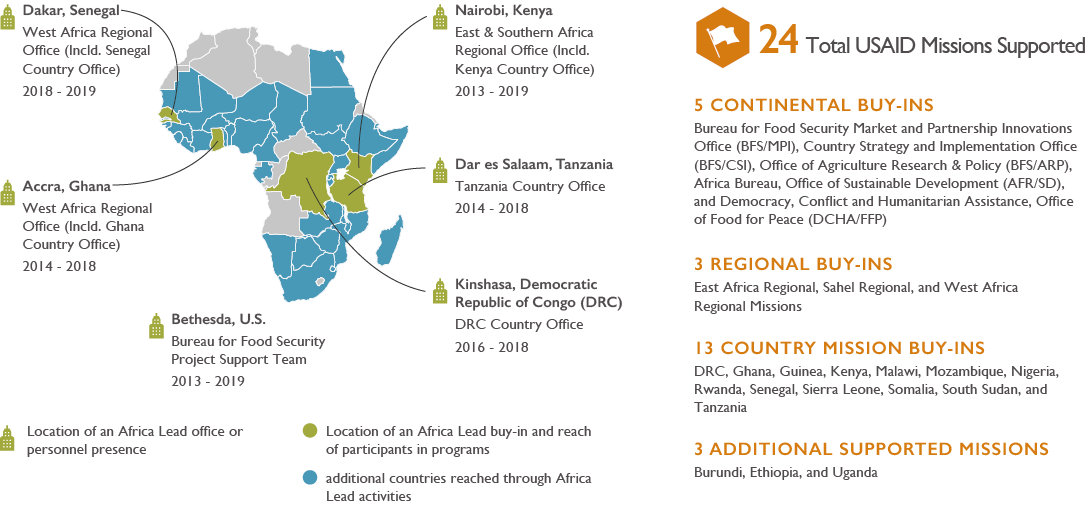

As a cooperative agreement and buy-in mechanism through the Bureau for Food Security (BFS) the project’s scope was continental. It had an original ceiling of $70 million that was expanded to $95 million in 2017. While it is a BFS core-funded program, Africa Lead was largely funded through buy-ins from bilateral Feed the Future countries in Africa and Regional Missions. Over the life of the project, Africa Lead had various in-country and regional offices that allowed our staff to work directly with continental, regional, national, and sub-national stakeholders, including the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and Feed the Future teams.

African Heads of State in 2003 launched the Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP), Africa’s policy framework for agricultural transformation, wealth creation, food security and nutrition, economic growth and prosperity for all. Africa Lead II’s goal was to support African-led policy transformation, where individuals, institutions, and networks are the driving force advancing Africa’s food security and resilience. Ultimately, these leaders, organizations, and groups are responsible for developing and sustaining policy priorities for reducing poverty and increasing nutrition through agriculture and achieving the goals of CAADP.

Africa Lead’s ultimate objective was to support African-led and African-owned policy processes and solutions to transform African agriculture, food security, and resilience. From the continental policy system level to the sub-national system level, Africa Lead set out to elevate the focus on policy change and country capacity to manage the policy change process.

Africa Lead’s ultimate objective was to support African-led and African-owned policy processes and solutions to transform African agriculture, food security, and resilience. From the continental policy system level to the sub-national system level, Africa Lead set out to elevate the focus on policy change and country capacity to manage the policy change process.

The CAADP Malabo Commitments set out to ensure inclusive agricultural transformation, involving the private sector, women, and youth. In all activities, Africa Lead set out to engage and support underrepresented voices in agriculture policy and agriculture development.

The CAADP Malabo Commitments set out to ensure inclusive agricultural transformation, involving the private sector, women, and youth. In all activities, Africa Lead set out to engage and support underrepresented voices in agriculture policy and agriculture development.

In 2014, the Malabo Declaration introduced seven high-level commitment areas under the Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) that span a wide range of issues, policies, and programs relevant to agricultural transformation in Africa with very specific targeted results that would be measured. Africa Lead’s programming support from the country to the continental level aligned to the CAADP Malabo commitments.

In 2014, the Malabo Declaration introduced seven high-level commitment areas under the Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) that span a wide range of issues, policies, and programs relevant to agricultural transformation in Africa with very specific targeted results that would be measured. Africa Lead’s programming support from the country to the continental level aligned to the CAADP Malabo commitments.

Africa Lead II (2013-2019) evolved from the predecessor project, Africa Lead I (2010-2013). The foundation of Africa Lead I’s success was primarily in leadership capacity building. In its initial design, Africa Lead II carried forward much of the programs, while expanding support to strengthen institutional capacity, the management of policy change and alignment processes, and enhance the capacity and engagement of NSAs, including the private sector.

Africa Lead II (2013-2019) evolved from the predecessor project, Africa Lead I (2010-2013). The foundation of Africa Lead I’s success was primarily in leadership capacity building. In its initial design, Africa Lead II carried forward much of the programs, while expanding support to strengthen institutional capacity, the management of policy change and alignment processes, and enhance the capacity and engagement of NSAs, including the private sector.

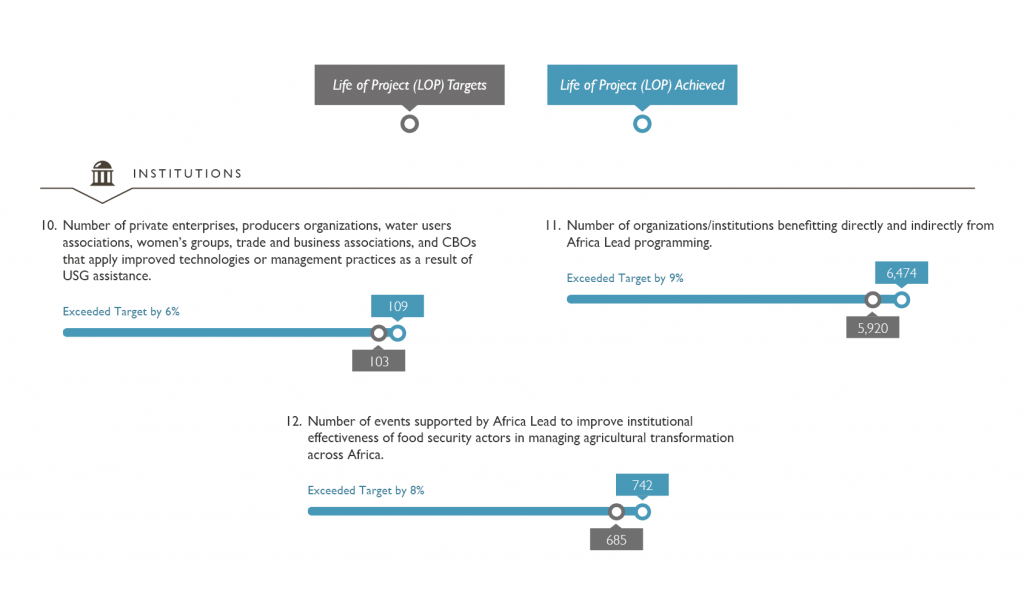

The complex and dynamic environments in which Africa Lead operated demand a flexible and adaptive monitoring and evaluation system that responds to both the accountability requirements and knowledge and learning needs of the program and our stakeholders. Africa Lead used both quantitative and qualitative methods to assess the contribution of our interventions to changes in behavior, attitudes, norms, and performance of individuals, groups, and organizations, but also the overarching objective of African agricultural transformation.

The complex and dynamic environments in which Africa Lead operated demand a flexible and adaptive monitoring and evaluation system that responds to both the accountability requirements and knowledge and learning needs of the program and our stakeholders. Africa Lead used both quantitative and qualitative methods to assess the contribution of our interventions to changes in behavior, attitudes, norms, and performance of individuals, groups, and organizations, but also the overarching objective of African agricultural transformation.

Africa Lead worked to strengthen both individual leadership capacity and organizational capacity of local institutions to support policy and institutional reform, which serve as drivers and accelerators of agricultural transformation.

Africa Lead’s work at the individual level focused on building resilient skills, especially around leadership, at all levels of the policy system. The program also focused on scaling and cascading trainings and entrenching the culture, concepts and programming with long-term sustainability in mind.

Africa Lead’s work at the individual level focused on building resilient skills, especially around leadership, at all levels of the policy system. The program also focused on scaling and cascading trainings and entrenching the culture, concepts and programming with long-term sustainability in mind.

Strong leaders must have enabling environments to work within. To complement Africa Lead’s leadership strengthening efforts, the program worked to improve capacity among targeted and key institutions involved in developing and managing national agricultural and food security programs.

Strong leaders must have enabling environments to work within. To complement Africa Lead’s leadership strengthening efforts, the program worked to improve capacity among targeted and key institutions involved in developing and managing national agricultural and food security programs.

Africa Lead complemented capacity building for effective leaders and institutions with support to activate networks and collective action. Africa Lead developed and strengthened transformative partnerships and networks such as non-state actor platforms and women and youth networks that make collective action possible. Africa Lead mobilized policy actors, participants, and advocates traditionally underrepresented in policy dialogue and debate, including women, youth, private sector representatives, and community stakeholders.

Africa Lead sought to develop and strengthen the multi-sectoral, multi-stakeholder collaborative networks, practices, and platforms that make collaborative action possible. These mechanisms help build strong linkages among policy system actors and institutions, as well as streamline communication, facilitate the mobilization of resources, and engender broad stakeholder support for policy priorities, including among groups like women and youth often excluded from policy conversations.

Africa Lead sought to develop and strengthen the multi-sectoral, multi-stakeholder collaborative networks, practices, and platforms that make collaborative action possible. These mechanisms help build strong linkages among policy system actors and institutions, as well as streamline communication, facilitate the mobilization of resources, and engender broad stakeholder support for policy priorities, including among groups like women and youth often excluded from policy conversations.

Broad participation in collaborative networks allows stakeholders to interact with one another and engage the government with evidence-based positions on existing and potential policies. Africa Lead mobilized policy actors, participants, and advocates—such as NSAs, the private sector, women, and youth—to participate more fully in agricultural sector decision making processes.

Broad participation in collaborative networks allows stakeholders to interact with one another and engage the government with evidence-based positions on existing and potential policies. Africa Lead mobilized policy actors, participants, and advocates—such as NSAs, the private sector, women, and youth—to participate more fully in agricultural sector decision making processes.

Africa Lead supported inclusive sets of stakeholders in developing, testing, and refining local solutions, whether specific policies or policy-making processes, within the framework of improved collaborative governance. In doing so, the project played the role of catalyst and connector for learning and innovations in individual leadership behavior, institutional performance, and policy processes.

Collaborative governance involves the government, community, and private sectors working together to achieve more than a single sector could achieve on its own. Africa Lead fostered collaborative governance by supporting inclusive public private dialogue and planning processes, while also building on its approaches to leadership strengthening, collaboration, coordination, and facilitative leadership.

Collaborative governance involves the government, community, and private sectors working together to achieve more than a single sector could achieve on its own. Africa Lead fostered collaborative governance by supporting inclusive public private dialogue and planning processes, while also building on its approaches to leadership strengthening, collaboration, coordination, and facilitative leadership.

Africa Lead promoted learning and adaptation by building capacity for M&E in government organizations, supporting NSAs to participate and bring evidence to dialogue and policy-making processes, organizing and facilitating learning events and networking activities, and creating and disseminating tools to raise awareness of CAADP.

Africa Lead promoted learning and adaptation by building capacity for M&E in government organizations, supporting NSAs to participate and bring evidence to dialogue and policy-making processes, organizing and facilitating learning events and networking activities, and creating and disseminating tools to raise awareness of CAADP.

Africa Lead supported African Union Commission’s Department of Rural Economy and Agriculture (AUC DREA) and countries across the continent in meeting the Malabo Declaration commitments and CAADP goals.

Africa Lead supported African Union Commission’s Department of Rural Economy and Agriculture (AUC DREA) and countries across the continent in meeting the Malabo Declaration commitments and CAADP goals.

Africa Lead is Feed the Future’s primary capacity building program in sub-Saharan Africa. Feed the Future (FTF) is the U.S. Government’s global hunger and food security initiative.

WWW.FEEDTHEFUTURE.GOV | WWW.AFRICALEADFTF.ORG

USAID’s focus on self-reliance presents a new vision for development and humanitarian assistance: building a country’s capacity to plan, finance, and implement solutions to local development challenges, and ensuring that there is a commitment to see these solutions through effectively, inclusively, and with accountability.

Africa Lead’s ultimate objective was to support African-led and African-owned policy processes and solutions to transform African agriculture, food security, and resilience.

From the continental policy system level to the sub-national system level, Africa Lead set out to elevate the focus on policy change and country capacity to manage the policy change process. This allowed for an increase in the role and contributions of non-state actors (NSAs) to agriculture transformation – including the private sector. Success at every level was more likely when Africa Lead worked in direct collaboration with African partners in government and civil society. Additionally, coordination with USAID and other donor stakeholders, as well as donor implementers, was essential to ensure the alignment of policy and capacity building efforts focused on improving food security and resilience outcomes. Improving these outcomes required that countries and African partners brought their full suite of resources to bear, including fully inclusive human and institutional resources.

At the continental level, Africa Lead worked in partnership with the African Union Commission’s Department of Rural Economy and Agriculture (AUC DREA) and in coordination with USAID’s BFS. Africa Lead supported the capacity and engagement of NSAs in efforts related to the CAADP Biennial Review through various fora, including through the establishment and support of the CAADP Non-State Actors Coalition (CNC).

Working together with Regional Intergovernmental Organizations (RIGOs) / Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and USAID, Africa Lead’s regional missions, Africa Lead staff, and programs supported collaboration between government, non-government and donor actors and institutions to engage in regional trade, food safety, and CAADP policy coordination and collaboration.

With national plans and priorities at the forefront of many of our local partners’ agendas, Africa Lead’s country programs and staff supported country-level policy priorities and explored ways to link these objectives to sub-national, regional, and continental frameworks. In collaboration with USAID bilateral priorities, Africa Lead supported government agencies, NSAs, and individual leaders leading and contributing to national policy efforts.

Many of Africa Lead’s programs reached actors and organizations at the sub-national level through our distributed and targeted trainings to provide education and capacity on national, regional, and continental policy priorities and frameworks. Additionally, engagement of these actors in national planning processes was incredibly important to comprehensive and informed policy processes and decision making. Africa Lead also explored grant programs to support sub-national NSAs to develop policy priorities from the grass roots and farmer level to feed into processes from the country to continental level.

With smallholder farmers at the heart of Africa’s agricultural transformation, the continent has the ability to feed every man, woman, and child. Yet, Africa is still a net importer of food, spending up to USD 35 billion annually on food, a number that is expected to rise to 110 billion by 2025.

With a focus on rising malnutrition rates and the great opportunity to transform Africa’s economy through agriculture, African Heads of State in 2003 launched the CAADP, Africa’s policy framework for agricultural transformation, wealth creation, food security and nutrition, economic growth and prosperity for all.

“The more critical aspect of CAADP is that it is an attempt by Africa to use agriculture to drive economic growth and transformation within countries. And when you’ve got growth and transformation, then the biggest beneficiaries should be the farmers, the majority of whom are smallholder farmers,” says Robert Ouma, Africa Lead’s Senior Policy Advisor.

From 2003 – 2013, with broad goals and a few specific ones, CAADP focused attention and galvanized action on increasing public investment into agriculture and urging faster agricultural growth as agricultural production became an important issue on the continental agenda. In 2014, realizing that agricultural transformation was a more complex, multi-faceted challenge, African leaders with the support of Africa Lead, rejuvenated CAADP through the Malabo Declaration.

The Malabo Declaration broadened the goals of CAADP to include seven high-level commitment areas that span a wide range of issues, policies, and programs relevant to agricultural transformation in Africa with very specific targeted results that would be measured.

To measure results and outcomes against its goals, CAADP established a results framework known as the Biennial Review. The first Biennial Review report released in 2018 measured progress on CAADP against 43 indicators across the seven commitments of the Malabo Declaration. The findings were intended to feed information platforms established under CAADP and those engaged with agricultural and rural development in Africa. The review will continue to occur every two years until 2025.

As one of Feed the Future’s capacity support programs to CAADP, Africa Lead worked as a key partner to enhance and advance the first Biennial Review process. Working with the AU and other partners, Africa Lead organized the initial training of trainers for the reporting process, facilitated six regional trainings in the data processing and reporting tools, and engaged its country facilitators to support the national CAADP teams in Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Nigeria, Malawi, and Senegal to get the Biennial Review report to the finish line.

While the 2018 report showed that less than half of the 47 AU member states that reported were on track to meet the Malabo Declaration goals and targets by 2025, completing the first review process represented a major accomplishment in measuring progress toward achieving the specific goals set by African nations. The accompanying Africa Agriculture Transformation Scorecard (AATS) also revealed that each country was facing context-specific challenges. For that reason, each country profile in the report included three recommendations on what was needed to stay on track, or where improvements could be made to meet the Malabo targets.

“The scorecard is a transparency mechanism to drive transformation. It encourages heads of states and governments to assess original commitments made versus performance,” said AUC DREA’s Dr. Godfrey Bahiigwa in a 2018 Agrilinks blog post. The hope is, he continued, that with the Biennial Review, “Available to all stakeholders in agriculture…[it] will stimulate dialogue, collaborative problem solving and a more inclusive African-led process to increase investment in agriculture.”

The 2nd Biennial Review process and accompanying report (to be released in January 2020) was also supported by Africa Lead facilitating country reporting trainings for over 200 people from nearly 50 countries. Africa Lead also provided facilitation support for the15th CAADP Partnership Platform (PP) meeting in June 2019, where a new CAADP communications toolkit developed with communications support by Africa Lead, was launched. Available in both English and French, the toolkit provides an online interactive application to track African governments’ progress towards CAADP goals, an overview of the results of the 2018 Biennial Review, and up to date information about the 2nd Biennial Review process.

The Biennial Review process has triggered dialogue that will be more inclusive and will engage a range of non-state actors, in particular civil society and the private sector. This will, hopefully, be a big win for Africa’s agriculture and the millions of people across the continent that depend on it for their livelihood.

During Africa Lead’s Capstone Learning event in October 2019, Christopher Shepherd-Pratt, Policy Chief of USAID’s Bureau for Food Security, reflected on the Biennial Review’s significance, “What’s really encouraging for […] some of the other processes we’re seeing in CAADP right now [is] we’re seeing this type of [adaptive management] approach embodied in a continent-wide agenda. It says that accountability is important and that there’s a willingness to change and learn.”

Learn more at www.africaleadftf.org/caadp

The CAADP Malabo Commitments set out to ensure inclusive agricultural transformation, involving the private sector, women, and youth. In all activities, Africa Lead set out to engage and support underrepresented voices in agriculture policy and agriculture development. Here’s a snapshot of some of the project’s work to advance inclusive agricultural transformation:

In sub-Saharan Africa women are heavily involved in food production, processing, and marketing. Yet, on average, only 15% of African women are landholders and are all too often left out of decisions and policy making. In African agricultural research institutions alone, women represent 24% of researchers and only 14% hold leadership positions.

Africa Lead programs and activities consciously targeted support and engagement of women leaders in government and NSA organizations. The program also sought to educate and sensitize leaders, organizations, and governments on the importance of incorporating and providing space for a more gender inclusive approach that truly represents the significant share women hold in Africa’s agricultural transformation, in the field and in the boardroom.

Government alone can not be responsible for guiding, leading, and implementing transformational agendas. That’s one of the reasons why Africa Lead focused on including the private sector in policy discussions and capacity building, reaching over 1,800 private sector companies and organizations in its work. Africa Lead facilitated the multisectoral development of National Agricultural Development Plans in six countries, with deep engagement of the private sector.

1,800 private sector companies engaged.

Since the launch of CAADP in 2003, African nations and leaders have been striving and working together to achieve agricultural transformation at the country level. However, in the first ten years it was difficult to understand how Africa was progressing on achieving the broad commitments and goals set out in 2003. In 2014, the African Union and member states through the Malabo Commitment, recommitted to a clear and measurable set of goals, organized in seven commitment categories, to achieve CAADP by 2025. Africa Lead played an important role in facilitating the initial development of these goals and the ongoing advancement and monitoring of progress. Additionally, Africa Lead’s programming support from the country to the continental level aligned to the CAADP Malabo commitments in the following ways:

The TOC also reflects that Africa Lead’s unique “Approaches” are central to the ability to deliver effective programming and activities in these pillars.

By design, Africa Lead activities were demand-driven. The project was seen as a flexible mechanism to provide demand-driven support to various USAID offices and their local partners at the bi-lateral, regional, and continental level in support of agricultural transformation. In order to appreciate the whole of Africa Lead’s impact, individual activities implemented by Africa Lead, USAID, and Feed the Future must be viewed within the larger context of the continental-wide goals which drive them. In this way,n Africa Lead as a project was truly greater than the sum of its parts.

Annual and Quarterly Buy-In Reviews and Reporting

Africa Lead performed regular and required quarterly and annual reporting from the inception of the program in 2013. Across each of Africa Lead’s regional and buy-in offices (East and Southern Africa, West Africa, and Continental), each office was encouraged to hold quarterly review meetings to reflect on successes and achievements during the previous quarter. During these quarterly review sessions staff also explored areas for improvement and invited stakeholders and other projects to attend the sessions to inform coordination and future planning. At the continental level, BFS staff were included in regular meetings, including an annual review session at the end of each fiscal year.2013 – 2017 Program Review

After four years of implementation, working with many partners since 2010 under the first phase of Africa Lead, the goal of the Program Review was to gather information, feedback, and input on Africa Lead’s impact and broader learning about progress toward agricultural transformation. Between April and June 2017, Africa Lead conducted the Program Review which engaged a total of 153 individuals, representing 83 organizations, through a total of 64 interviews in nine countries across 10 national and regional programs. The review drew on in-depth key informant interviews and focus group discussions with Africa Lead’s partners, exploring local context and country or region-specific findings and conclusions to understand changes attributable to the program. Utilizing a newly developed Benchmarking Performance for Agricultural Transformation (BPAT) tool, the Program Review led facilitated self-assessments with over 50 of Africa Lead’s key beneficiaries, focusing on the following themes linked to improving institutional effectiveness for agricultural transformation: Transformational Leadership; Inclusivity; Coordination; Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E); Evidence-based Adaptation; and Resource and Investment Attraction. The results which can be found in the Program Review report, were intended to help inform Africa Lead and other organizations on effective strategies for improving the performance of individuals, organizations, and networks working to align to CAADP and to transform agricultural programs and policies to improve food security outcomes. The newly developed BPAT, used for self-assessment across key Africa Lead partners, was designed to serve as a gauge to monitor progress over time.2018 Lessons Learned Event

In early 2018, Africa Lead hosted a four-day stakeholder-driven event involving 80 individuals from USAID Missions, partner institutions, government agencies and organizations. The facilitated learning event reviewed lessons learned from the Program Review, as well as identified other emerging trends and lessons from Africa Lead’s work. The goal was to gather lessons learned about Africa Lead’s programming and provide recommendations for future food security capacity building programming. Africa Lead developed eight thought pieces and established breakout groups over three days, focused on the following areas: Capacity Development (Champions for Change, Organizational Development, Communications); Facilitative Leadership; Continental to Country Coordination; Inclusive Policy Process; and Sustainability (Scaling, Mainstreaming, and Institutionalizing). Results of lessons learned were incorporated into the final year of programming (program year six) and are reflected in the lessons learned sections in this report.2019 Final Program Year Learning Series

The objective of the Africa Lead Final Year Learning Series, held over a six-month period from June – November 2019, was to educate Africa Lead’s partners about how the program evolved over the last six years and how the flexible mechanism allowed USAID and Feed the Future to respond to the rapidly changing African-led food security and resilience policy landscape. The learning series sought to transfer experience, knowledge, best practices, and lessons learned through a series of online webinars and in-person events (across Africa and a select number of events in Washington, DC), as well as through online materials (such as blogs and articles) and thought-leadership pieces. Kicked off by a webinar in partnership with Agrilinks and the African Union, more than ten events were held from June 2019 – November 2019, concluding with two capstone learning events in Washington, DC. The first was a final learning event about African-led policy efforts held at the National Press Club and hosted in partnership with the African Union. A final resilience learning event focused on resilience partnership models in conflict areas was held in partnership with USAID’s Center for Resilience. Learning event material is available on Africa Lead’s website at www.africaleadftf.org/learning.“Africa Lead is uniquely broad in terms of your reach, stakeholders, what you’re hearing from the ground, all the way up to high-level governments and intergovernmental organizations. So, you’re uniquely positioned as a learning activity to provide feedback to USAID as well, on gaps and opportunities … not to just learn internally, but identifying gaps and opportunities for USAID as well.”

– Luis Tolley, USAID East AfricaAfrica Lead’s original Performance Monitoring Plan (PMP) was approved in FY2015. In 2017, Africa Lead redesigned and expanded the original PMP to better address evaluation and learning objectives, and to reconcile data collection and indicator reporting standards with lessons learned during implementation. The 2017 revised Performance Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning Plan (PMELP) retained the focus on CAADP and Feed the Future Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) frameworks and indicators, while incorporating improved data collection processes and additional analysis (such as the design of Africa Lead’s internal evaluation, called the Program Review) to measure significant project outcomes.

In Africa Lead’s final year (FY2019) the project updated the PMELP to reflect the recently validated TOC, plans for end of program learning series, and updated targets for additional FY19 activities.

While it retained the same spirit and focus as previous iterations, the 2019 revised PMELP incorporated a number of important adjustments including:

Africa Lead also reported to USAID’s Feed the Future Monitoring System (FTFMS) on an annual basis. Monitoring data for FTFMS was disaggregated by Mission, and reported separately for each Mission, including BFS activities funded centrally by USAID/Washington.

Indicators for monitoring and evaluating Africa Lead programs were classified into output, outcome, and context indicators. Output indicators focus on the delivery of tasks and activities that were under the direct control of Africa Lead. These indicators measured progress against performance targets, such as the number of individuals who received training and the number and type of institutions and organizations that received capacity building support from the project.

Outcome indicators measured intermediate results such as changes in knowledge, behavior, and practice at the individual and organizational levels due to training, knowledge transfer, technical assistance, and capacity building that are directly attributable to the project.

Context indicators assessed change in areas that Africa Lead sought to contribute to indirectly, but were beyond the project’s direct influence. While these outcomes are relevant and important to better understanding Africa Lead’s results, they are not attributable to the project. Several of Africa Lead’s context indicators were inspired by Feed the Future and Malabo Declaration indicators, but they were in fact custom context indicators.

Africa Lead’s 2019 revised PMELP incorporated three of the GFSS indicators published in the March 2018 Feed the Future Indicator Handbook.

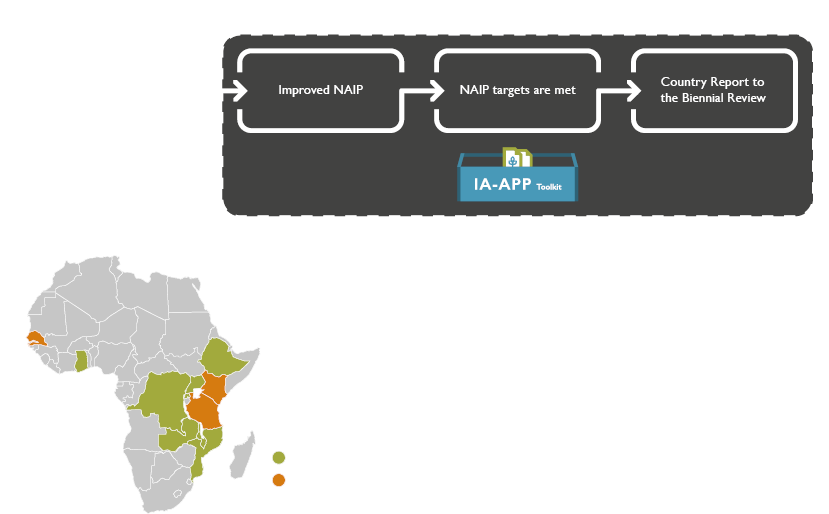

In addition, Africa Lead’s Institutional Architecture Assessing, Prioritization and Planning (IA-APP) toolkit and approach, which was piloted in Kenya, Senegal, Tanzania, and Uganda, includes a self-assessment of NSA participation in policy development and implementation process, which effectively captures NSA feedback on mutual accountability process as well. The data and results of the IA-APP process were also important monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) information for Africa Lead and local stakeholders.

“In 2018, Africa Lead held a four-day Lessons Learned Event (LLE) in Kenya to capture lessons learned and generate recommendations for near and long-term programming.”

Africa Lead’s work at the individual level focused on building resilient skills, especially around leadership, at all levels of the policy system. Research has shown that investments in individual leadership and change management capabilities generate substantial rates of return for organizational development and help to prepare future workforces. Africa Lead focused on strengthening the leadership and management capacity of key policy actors and stakeholders with targeted training focused on improving individual leadership capabilities.

Africa Lead’s focus was not only on delivering leadership training and building the capacity of leaders. Africa Lead also focused on scaling and cascading trainings and entrenching the culture, concepts and programming of Africa Lead’s approaches with long-term sustainability in mind. This involved working to build networks of leaders and facilitators, and to “institutionalize” the training curricula within local institutions and other donor programs.

CONTINENTAL

Champions for Change

The “Champions for Change” (C4C) leadership training was a cornerstone activity of Africa Lead, based on the core curriculum from Africa Lead I. A five-day customizable course given by trained facilitators, the C4C training was designed to train and motivate individual leaders at all levels of agriculture – farmers, government, NSA groups, and other key food security institutions – to catalyze the transformation of the agriculture sector and improve food security.

CONTINENTAL

Facilitator and Trainer Network

Nearly all of the Africa Lead trainings were delivered by Africa Lead-trained facilitators. The program invested in building the capacity of experienced facilitators and trainers and creating a network that was able to understand and facilitate discussions relating to agricultural transformation. This network of nearly 100 trainers across the continent conducted training in over 27 different content areas for approximately 312 different organizations, institutions, and agencies.

WEST AFRICA

West African Universities & Champions for Change

In an effort to institutionalize transformative food security leadership development, Africa Lead worked to build the sustainability of the C4C Leadership training by institutionalizing the C4C modules into university curriculum in three countries including Ghana, Senegal, and Nigeria. In total, six universities have adopted the C4C modules into their core agricultural curriculum and 600 students have completed the courses.

EAST AFRICA

Executive Leadership Course for Africa’s Food Security

In the sixth and final program year, Africa Lead piloted a new leadership training program based on lessons learned from Africa Lead I and II. The intensive six-month program combined in-person workshops and online learning with action learning projects and on-the-job feedback. Delivered to a cohort of 20 competitively selected leaders from East and Southern Africa, the training required participants to pay for or enlist their organization or company to pay for a portion of their tuition. At the conclusion of the course, Africa Lead collected feedback from peers and colleagues of the participants. Ninety-five percent of respondents reported an improvement in some combination of leadership ability, effectiveness, and motivation of the relevant participant during the period of the course.

KENYA

Kenya Institutionalization of the Champions for Change Leadership Training

To develop leadership capacity in Kenya’s agricultural sector, Africa Lead provided C4C training to individuals throughout the country, including staff at the Council of Governor’s Secretariat, County Executive Committee members, and NSAs, as well as many others. After the success of initial training sessions with top county officials, stakeholders requested that the training be replicated and expanded to county executives, officers, and other officials in all 47 counties. Africa Lead trained 60 trainers and worked with the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries (MoALF) to roll out a national C4C training program. This training is ongoing with support from the German development agency GIZ and the Agriculture Sector Development Program (ADSP).

Strong leaders must have enabling environments to work within. To complement Africa Lead’s leadership strengthening efforts, the program worked to improve capacity among targeted and key institutions involved in developing and managing national agricultural and food security programs. Africa Lead applied different approaches across the program to assess organizational capacity, diagnose issues, and ultimately, prepare a plan and recommendations to support organizational strengthening and change management.

Africa Lead focused on strengthening organizations and institutions in the following ways:

TANZANIA

Agriculture Non-State Actors Forum (ANSAF)

ANSAF, an umbrella organization of farmer groups, NGOs, and private companies in Tanzania, received a variety of assistance from Africa Lead including a C4C training, CAADP sensitization, a stakeholder mapping, and technical assistance and facilitation support for several critical learning events. Africa Lead and ANSAF also worked together to create and facilitate the Policy Action Group, which coordinates research for agriculture policy reform. With support from Africa Lead, ANSAF successfully influenced the Government of Tanzania to lift the export ban on cereals, as well as enhance legislation and certification of fertilizers. The lift of the export ban on cereals led to increased income for farmers and an increased food supply for regional trading partners.

EAST AFRICA

The East Africa Community (EAC)

Africa Lead conducted an Institutional Architecture Assessment (IAA) focused on the Department of EAC Secretariat that provided useful findings that led to immediate action on several key recommendations, such as the development of a new Regional CAADP Compact and a revised Food Security Action Plan and Results Framework, which outlines specific indicators to track progress against commitments to the overall investment plan for the region. The recommendations from the IAA also helped the EAC to develop a revised Regional Agricultural Investment Plan to prioritize resources and investments to improve food security at the regional level.

KENYA

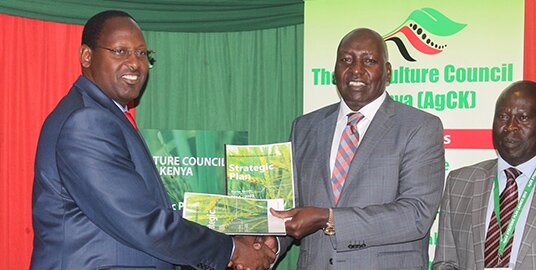

Agricultural Council of Kenya (AgCK)

Africa Lead provided critical organizational development for AgCK by advising the organization on developing a governance structure, annual work plans, a business plan, and resource mobilization and institutional sustainability strategies. Africa Lead also helped AgCK establish a secretariat to guide its work and increase engagement with sub-national NSAs. With Africa Lead’s support, AgCK now serves as an apex body to facilitate private sector and youth and farmer group participation in the country’s processes to develop its Agriculture Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy (ASTGS) and NAIP.

WEST & CENTRAL AFRICA

West and Central Africa Council for Agricultural Research and Development (CORAF)

A council with 22 member states in West and Central Africa, CORAF has a mission to promote and enable sustainable improvements in agricultural productivity, competitiveness, and markets in West and Central Africa. Africa Lead provided targeted technical assistance including support to the Board of Directors via a Board Governance Capacity Development Workshop, Advanced Leadership and Team Building Training, M&E/Results Based Management (RBM) training, and an institutional audit to identify areas of improvement in CORAF’s management structure and practices to reinforce its financial sustainability and mandate as the lead agricultural research institution in West Africa.

GUINEA

Bureau de Strategie et Developpement (BSD)

The BSD was an existing intra-governmental coordination mechanism between the four key ministries involved in agricultural issues. Africa Lead conducted a participatory training needs assessment for BSD staff that showed that the BSDs in charge of agriculture in Guinea faced challenges in the formulation and monitoring and evaluation of agriculture development policies. The BSD also faced challenges in terms of lack of trust, conflict, and confusion among the members about their roles. Africa Lead designed a capacity-building plan for the BSD to address these weaknesses. In addition, the process to review and revise the Plan National d’Investissement Agricole, de Sécurité Alimentaire et de Nutrition (PNIASAN) – generally referred to as the National Agriculture Investment Plan (NAIP) in Guinea – helped the four ministries build a common vision for success across each organization. The strategic planning exercise and other facilitated sessions supported by Africa Lead helped clarify roles and fostered a sense of collective ownership over the PNIASAN II development, and ultimately, its implementation.

Justus Monda walks through a dry, shrub-filled plot of land to meet his neighbors who have gathered to help him harvest this season’s maize. The field was once filled with pyrethrum flowers, but he’s had to turn to maize as his main crop due to poor pyrethrum yields and prices. Growing up in the fertile highlands of Southwestern Kenya famous for bananas, Justus was raised by crop-growing parents who always ensured they had enough food to eat, and some to sell to cover basic needs. After finishing his education, Justus moved to Kenya’s Central Rift Valley to work as a banker, and bought his first piece of land to venture into farming pyrethrum.

Thirty-two years later, Justus is a leading advocate for farmers as the chair of the Agriculture Council of Kenya (AgCK), an institution supported by USAID Kenya through Feed the Future’s Africa Lead program. AgCK was established in 2015 by six agriculture sector interest groups. Now the organization includes 10 apex organizations and 13 affiliate organizations, representing the interests of about 2.8 million individuals involved in agriculture across Kenya.

“AgCK is unique because it was formed by the leaders of Kenya’s agriculture interest groups – farmers and producers, the private sector, extension services, academia and research, youth, women, agro-dealers – to speak with one voice. We see our interests as the same, to create a more food-secure Kenya,” says Justus.

Justus, like many of his colleagues on AgCK’s Steering Committee, became a leader in Kenya’s agriculture sector because of the challenges he faced as a farmer. As a young farmer in the pyrethrum industry, he saw many ups and downs. In his early years, Justus enjoyed the great rewards of the little known crop; there was a ready market and farmers’ payments were always on time. In the years that followed, this “magical crop”, as he calls it, no longer fetched meaningful returns. Prices dwindled and the lack of a proper regulatory body meant that middlemen could cripple profits. These experiences inspired him to be a voice for farmers’ issues and a more organized agriculture sector, and in 2001 he formed the Kenya Pyrethrum Growers Association.

Over the years, millions of Kenya’s agriculturalists have been represented by various interest groups, depending on their crop or business. And while there has been individual success for the various organizations, many of the organizations realized they lacked a unified voice to coordinate lobbying, advocacy, and education efforts targeted at the various levels of government and agriculture planning. The result, according to Justus, has been an agriculture sector that is failing to feed Kenyans like it fed him when he was a child.

“It is a pity that 3.5 million people are staring at hunger. The government [is] running up and down distributing food,” says Justus. “But food can be produced, organized, and distributed by the farmers themselves, given the right infrastructure.”

Justus is clear to point out that AgCK is not an organization for leaders of agribusiness. Instead, it seeks to represent under-represented groups that make agriculture a major part of Kenya’s economy. Seventy-five percent of Kenyans derive all or part of their livelihoods from agriculture which also accounts for more than half of Kenya’s gross domestic product. Yet small farmers and those who rely on agribusiness struggle to reach policy makers with their grievances and solutions for better policies.

“Farmers’ problems at grassroot-level don’t seem to reach the decision makers at the top. We need a voice to take our plight and ideas to the national government for them to know our state as farmers,” says Steven Ndambuki, a farmer from Makueni County in Eastern Kenya, who is represented by Kenya’s Small Scale Farmers Federation, a member of AgCK’s Steering Committee.

Africa Lead’s support came just as AgCK was beginning to take shape in 2016. As part of the program’s continental focus on supporting NSAs’ engagement in agricultural policy dialogue, Africa Lead provided AgCK with technical support for organizational development.

Africa Lead supported AgCK through stakeholder consultations, membership and communication strategy development, and development of a new website to host the organization’s materials and updates.

Justus points out that Africa Lead’s support not only helped AgCK grow and become more stable, it also linked them to other African NSAs through the CAADP Non-State Actors Coalition (CNC), another Africa Lead partner. He also points out that the support helped to improve Kenyan NSAs’ engagement in CAADP and associated processes.

“We now have a space at the presidential roundtable, so that…issues that affect farmers at whatever level, are picked from there,” says Justus.

With a growing membership, and leadership structure made up of champions like Justus at the helm, the future looks bright for AgCK. More importantly, Justus and his colleagues know that they have now found their unified voice.

In a remote Maasai village in Longido, Tanzania, Linda Simon, a 2014 Young African Leadership Initiative (YALI) Fellow, is working to ensure that no school child goes hungry.

Linda launched the organization Education Village, to support rural schools to improve their food systems. She understands that education and nutrition are closely linked; when children go to school on an empty stomach and go without lunch, concentration and performance is poor, school attendance is low, and dropout rates are high.

As a public health student working in a local hospital, Linda noticed that children treated for malnutrition were being readmitted weeks after being discharged. Linda knew that many families in could not afford to provide lunch for their children. She thought if schools could improve their food systems, they could both reduce malnutrition among students and increase access to education.

Linda is one of six YALI Fellows in Tanzania that received technical support from USAID Tanzania through Africa Lead, USAID and Feed the Future’s food security capacity building program, focused on strengthening the strategic planning and sustainability of her organization.

The first school targeted by Education Village is Linda’s former school, Tinga Tinga Primary School. Thanks to Education Village and support from Africa Lead’s technical consultant, Madawa Mhanga, Tinga Tinga now feeds its pupils school lunch from a kitchen garden made of five garden beds which benefit from cutting-edge micro-drip irrigation.

Linda explains that “the bigger picture is to be able to scale up and establish more rigorous ways of funding school feeding programs […] and look for projects that are income generating.”

In line with this vision, Africa Lead helped Education Village develop a business plan to scale the project from feeding pupils to generating income by selling drip irrigation systems to small-scale farmers and schools. Current vegetable production will also increase to one acre (4900 sq. meters) of high value vegetable production.

With a plan in place this project was funded by Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) and Africa Lead’s support played a key role in developing partnerships with the East African Community (EAC). Africa Lead supported Education Village develop Cross Border Business Boom Clubs, a platform to enhance business-to-business networks among young entrepreneurs in East Africa. One of these clubs, Brides with Skills, is funded by the EAC and helps young mothers develop skills to earn a living, while teaching them how to improve their children’s nutrition.

Education Village is now focused on ensuring everyone has access to a quality education and nutrition in Northern Tanzania, which should give many students something very important to chew on.

Young Champions for Change Fellows Training, Tanzania, 2014

Rose is passionate about the use of information communication technology (ICT) for agriculture. Today, she runs Agrinfo Company LTD, a technology company she started to organize the agribusiness sector’s information and make it accessible and easily searchable for farmers.

“The Champions for Change training empowered me to pursue ICT for agriculture, specifically the use of drones for agriculture. It also equipped me with leadership skills and knowledge on how to be an agent for change. Today, we are working in three villages in Chemba district, and piloting a maize pre-harvest loss project in Dodoma (Tanzania) that will use drone data to calibrate satellite imagery.”

Bomet County Kenya – Champions for Change Training Kenya, 2016

In 2015 and 2016, Africa Lead delivered 35 C4C trainings in partnership with 22 of Kenya’s 47 county governments reaching 1,075 government employees and NSA leaders.

“After the Champions for Change training, my county [Bomet County] realized that transforming the agriculture sector needed more extension officers and technical staff. We trained and employed more [youth] extension workers reducing the extension officer to farmer ratio from 1:2,000 to 1:1,200,” said Beatrice Kirui who participated in the training at the time as the Bomet County Executive Commissioner for Agriculture and Agribusiness. As a result of action planning completed in the trainings, the county enhanced productivity in the dairy, feed, and fodder sectors, and identified opportunities for local sale and export of sweet potatoes produced in the county, leading to the development of a new sweet potato bread factory.

Training of Trainers Course, Continental 2016

With a PhD in Agriculture from the University of Reading, UK, Aichi Kitalyi a Tanzania-based Africa Lead facilitator and trainer, says the Training of Trainers (TOT) course gave her the skills that have allowed her to provide facilitation for various country-level policy efforts and several food security focused organizations including the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), World Bank, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), and Heifer International.

“The Champions for Change training matured me into a professional facilitator. I learned the meaning and values of emotional intelligence and got introduced to cognitive psychology concepts. I have facilitated more than 30 professional convenings, the biggest being the nationwide socialization convening for the Agriculture Sector Development Program (ASDP 2) in Tanzania.”

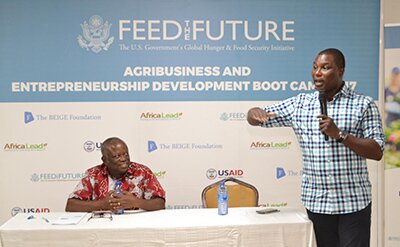

Agribusiness and Entrepreneurship Development Bootcamp, Ghana 2017

Before October 2017, Vozbeth Kofi Azumah had never thought of getting involved in agriculture. Then he participated in USAID/Ghana and Africa Lead’s Beige Foundation Agribusiness and Entrepreneurship Development Boot Camp, which he says is where his “agricultural journey started and was shaped by the training.”

“The good news,” he told Africa Lead in 2018, “is that after the training, the skills acquired have helped me to win a pitching competition worth 120,000 GHS (or $20,000 USD) as equity financing to support my startup livestock company Breeder’s Hub.” Vozbeth was the lead feature in the May 2019 New York Times article about Africa’s agripreneurs entitled Millennials ‘Make Farming Sexy’ in Africa, Where Tilling the Soil Once Meant Shame by Sarah Maslin Nir.

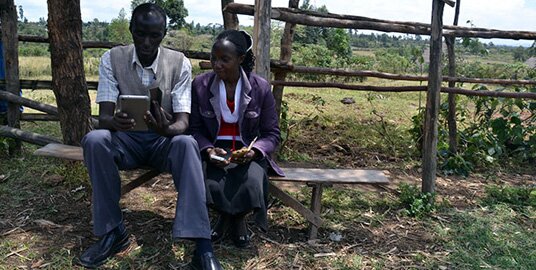

Fredrick Korir is a young extension agent from Bomet County, located in Kenya’s agricultural heartland. Bomet, spanning over 1600 square kilometers, has a diverse landscape featuring lush hills where maize, fruit trees and sweet potatoes grow. It is also home to fields that reach across high plains where wheat flourishes and herds of cattle graze. As one of the County’s ninety agricultural extension workers who interact directly with farmers to improve food security, Fred covers only a fraction of the county, but has four hundred farmers and a huge area to cover by foot, bus, or motorcycle.

It was the U.S. Government’s global food security and hunger initiative, Feed the Future, that helped Fred devise a plan to use a simple mobile phone app to solve his monumental task.

In 2015 Fred was a recent university graduate and had been out of work for close to two years. That all changed when the Bomet County government decided to hire a new group of youth agriculture extension agents. With the support of USAID Kenya and implemented by Feed the Future’s continental-wide capacity building, Africa Lead, these agriculture extension agents were provided the “Champions for Change” leadership training to help boost agricultural extension services in the county. Part of the training focused on strategic planning for and use of information communications technologies (ICT) in extension services.

With Kenya embracing the devolution of government services from the national to county level, each county has had the huge task of quickly creating systems to bring effective development to people at the local level. Initially, Africa Lead, as part of a multi-county training effort, offered the Champions for Change Leadership Training for 60 county officials from various arms of the Bomet County government. In this training members of the Ministry of Agribusiness created an action plan to hire the 35 youth extension agents who develop action plans in an Africa Lead training, which would later be tied to performance contracts.

Fred, who had received training on e-extension by the Kenyan government in 2012, created a plan to use ICT apps, not only to tell people about the work he was doing, but to improve farmer-to-farmer learning and increase the number of farmers he could reach. Fred first created a chat group of just the farmers he worked with. As it became more popular, he coordinated with his extension colleagues and they decided to form a county wide group called “Real Farmers”. The result has been game changing.

Now about five groups have been created across Bomet’s various WhatsApp groups. Additionally, other County staff use WhatsApp it to coordinate efforts, share pictures of issues on farms, and link farmers with commercial opportunities.

“The farmers are getting more information faster, as an extension officer I am able to address several challenges that farmers are facing. We can share experiences. Farmers can share experiences by [sharing] the problems they face to the group and participants can help identify the problem,” says Fredrick.

Fredrick estimates that prior to the training he saw 4-5 farmers per day going personally to their plots. Now, using his phone he can reach about 800 farmers a day instantaneously. He also reaches his various lists of farmers using bulk text messaging offered by Kenya’s Safaricom. The success of Bomet’s new extension agent training and the resulting technology innovations are part of a larger successful relationship between Feed the Future’s Africa Lead program and Bomet County.

Most importantly, from the field to the market, Bomet County is building better and more efficient ways to know “WhatsApp” when it comes to agriculture and food security.

Justin Urassa, an associate professor at Tanzania’s Sokoine University, believes that agriculture is a pathway out of poverty, specifically for Tanzania’s rural youth. Ask him if he understood that three years ago, and he’d say not to the level he does now. His lack of a technical background in agriculture and food security hasn’t been a barrier for this Tanzanian with a Phd. in Development from the University of Sussex, UK. In fact, he says it’s his experience as a professor coupled with the training he received from Africa Lead on food security facilitation that has allowed him to be an even more effective advocate and facilitator for food security leadership in Africa.

Justin’s story isn’t much different than the hundreds of facilitators trained by Africa Lead, all of whom make up the Feed the Future program’s growing network of food security facilitators. Since 2014 these trainers and facilitators have been at the head of hundreds of trainings and events, training thousands of leaders in food security across the continent. Like Justin, these food security teachers didn’t start as off as food security experts. Many however bring their own experience and strengths to the table and Africa Lead leverages that experience in its facilitator training program.

“In order to train individuals, we have needed to build the capacity of professionals who are actually trained to deliver these trainings. To help develop the skills of the trainers we have conducted what we call Training of Trainers (ToT) activities which involve taking qualified professionals from the university, private sector and government to train them on how to deliver this Champions for Change curriculum,” says Catherine Mbindyo, Africa Lead’s East and Southern Africa regional learning programs manager.

Experienced facilitators with proven track records are in great demand. Africa Lead is working to exponentially grow the impact that its trainers have, by preparing facilitators to be able to train other new trainers, through an Advanced ToT program. The training focused on sharing experiences and ensuring that the trainers learn from one another.

Justin Urassa participated in the Advanced ToT. Following the training, he and four other trainers from Tanzania returned home, to hold a cascade training for fellow Tanzanian trainers. As the network of trainers grows exponentially because of these types of efforts, Africa Lead is developing an online Trainer Directory, freely available to organizations seeking food security and facilitation expertise on the Africa Lead website.

“I believe in that future, that Tanzania can become nutritionally and food secure. When I want to create a sense of urgency [amongst my students], I borrow from my Africa Lead training,” says Justin reflecting on his training. “Leadership is the core, it’s not about resources that we don’t have the manpower to do it, the manpower is there to do it. At times it just lacks leadership, leadership is the cornerstone of transforming Africa to becoming a prosperous continent.”

With facilitators like Justin and his colleagues, leadership won’t be the only cornerstone to Africa becoming a prosperous continent. It will be a network of leaders and champions for food security who are laying the foundation.

In 2014, the African Union and member states committed to the Malabo Declaration – a measurable set of goals to achieve agricultural transformation under the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP). One of the seven commitments under the Malabo Declaration focuses on increasing the participation of women and youth in agriculture and agribusinesses as critical agents in inclusive agricultural growth and transformation. Africa Lead supported this Malabo commitment through various approaches – including institutionalization of the Champions for Change (C4C) Food Security, Leadership and Change Management training into tertiary agricultural sciences curriculums in West Africa.

The objective of the C4C is to build the capacity of champions — i.e., men and women leaders in agriculture — and the institutions in which they operate to develop, lead, and manage the policies, structures, and processes needed for agricultural transformation. Taking the C4C experienced-based, practical method approach model into an academic setting provides an opportunity to combine agricultural sciences theory with more practical, hands-on training.

A total of six top-ranked public universities from Senegal, Nigeria and Ghana have adopted C4C course modules into their curriculum, including the Higher Institute of Agriculture and Entrepreneurship at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Senegal (ISAE/UCAD), thee universities in Nigeria – Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU), the University of Nigeria-Nsukka (UNN) and the University of Benin-Nigeria (UNIBEN),

and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) and the University for Development Studies (UDS) – both in Ghana.

The initiative to integrate the C4C curriculum into university programs reflects a core element of Africa Lead’s strategy for supporting the African Union’s Comprehensive African Agriculture Development (CAADP) goal of transforming the continent’s agricultural sector into an engine for economic growth, development, improved nutrition and food security, through increased youth engagement and cultivating the next generation of leaders and entrepreneurs.

Young people in Africa tend not to view farming as a desirable job, but see it as back-breaking, low-wage work. In fact, there is money to be made in agriculture, and it is with youth participation that the agricultural sector will transform. Youth participation in agriculture is a win for the agriculture sector and a win for youth.

Africa Lead worked closely with all six universities in adapting, validating and integrating the training for each university, and in building in-house capacity to deliver the material. Africa Lead delivered five-day Trainings of Trainers (TOTs) to lectures and staff from each university –

fully equipping them to deliver both modules of the Champions for Change (C4C) curriculum. Module 1 consists of a single Teaching Unit on “Food Security and Nutrition” which includes six lessons. Module 2: “Leadership, Managing Change and Micro-Finance in Agriculture” includes 16 lessons. As of Sept 2019, more than 600 students had completed the C4C curriculum through the partner universities.

The most advanced in the C4C integration path is the Higher Institute of Agriculture and Entrepreneurship at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Senegal (ISAE/UCAD) – the first university to adopt the modules that are now mandatory for all its students at the undergraduate and graduate level. ISAE/UCAD has also established an internship program with the support of Africa Lead – placing students within host agribusinesses for a 10-week period to gain practical experience to help launch their careers in the agribusiness sector.

At an Africa Lead learning event in Senegal in October 2019, representatives from the six partner universities participated in a panel discussion around C4C institutionalization. The university representatives praised the initiative, and agreed that it reached new target groups at the higher education level – students and lecturers of agriculture and agribusiness, and is contributing to an updated perception of agriculture where the students see themselves as future agriculture sector technicians, specialists, and business owners. Recommendations coming from the discussion include that participating universities conduct inter-institution exchanges and knowledge sharing around integrating the different C4C modules, and that in addition to C4C capacity building, they develop curriculum around issues such as finance and land access.

At the October learning event, Africa Lead also spoke to a UCAD/ISAE graduate student, Abibatou Diatta who is originally from Senegal’s southern Casamance region. Ms. Diatta spoke about her experience with ISAE and C4C, as well as her plans once she completes her Masters Degree in agroecology. Ms. Diatta said that the C4C leadership course helps students see that while agriculture is difficult, one can be successful. She said “I want to show other young people that agriculture works, it pays – it’s difficult work, but it pays. It is also agriculture that will help Senegal’s economic development – especially in Casamance. The region of Casamance is an agricultural area that could feed the whole country. It doesn’t make sense to leave such a rich area to go search for money elsewhere. There is money there. I want to show this to people. In five years, I will have my farm there. My fruit trees will be producing, and I will harvest and sell and make money. I also want to share my knowledge and to have other young people come and work on my farm so that they can learn from me. I want my employees to be more like students”.

Since 2010, Africa Lead has been adapting its programming to build off lessons learned related to transforming leaders, which was the singular focus of Africa Lead I. The second phase of Africa Lead included a major shift in the design to focus on strengthening the institutions that leaders work within or are attempting to work with to effect change, rather than just the leader on their own. Leadership development, when complemented by improving institutions provides a comprehensive set of tools to transform both leaders and institutions. Good leadership achieves much more when exercised in the context of a functional and facilitative institutional environment.

Champions for Change Curriculum

This training curriculum has become a flagship offering of the Africa Lead program and can be customized to a variety of contexts and stakeholder groups to scale up the cadre of individuals who understand the impact of strategic thinking and planning related to CAADP. https://www.africaleadftf.org/knowledge-base/transformative-leadership-training-curriculum/.

This training curriculum has become a flagship offering of the Africa Lead program and can be customized to a variety of contexts and stakeholder groups to scale up the cadre of individuals who understand the impact of strategic thinking and planning related to CAADP. https://www.africaleadftf.org/knowledge-base/transformative-leadership-training-curriculum/.

Facilitative Leadership Learning Brief and Presentation

These resources draw upon examples of Africa Lead’s work in three countries to use facilitative leadership to better enable policy reform progress around agriculture and capture useful lessons around what enables this type of facilitation to work and what makes it challenging. https://usaidlearninglab.org/library/facilitative-leadership-using-facilitation-enable-strategic-collaboration.

These resources draw upon examples of Africa Lead’s work in three countries to use facilitative leadership to better enable policy reform progress around agriculture and capture useful lessons around what enables this type of facilitation to work and what makes it challenging. https://usaidlearninglab.org/library/facilitative-leadership-using-facilitation-enable-strategic-collaboration.

Benchmarking Performance for Agricultural Transformation (BPAT) Tool

The BPAT is a facilitated, self-assessment tool that helps key governmental and non-state actors assess their performance in implementing CAADP commitments. Africa Lead developed the BPAT in 2017 through the internal Program Review, and has developed a modified/abbreviated version to guide more interim follow-up with relevant organizations. https://www.africaleadftf.org/knowledge-base/benchmarking-performance-in-agricultural-transformation-bpat-tool/.

The BPAT is a facilitated, self-assessment tool that helps key governmental and non-state actors assess their performance in implementing CAADP commitments. Africa Lead developed the BPAT in 2017 through the internal Program Review, and has developed a modified/abbreviated version to guide more interim follow-up with relevant organizations. https://www.africaleadftf.org/knowledge-base/benchmarking-performance-in-agricultural-transformation-bpat-tool/.

Africa Lead Trainer Directory

Africa Lead has invested in building the capacity of experienced trainers/facilitators that are able to understand and facilitate discussions relating to agricultural transformation and have a proven track record in delivering capacity building training programs for multiple stakeholders within the agricultural sector. https://www.africaleadftf.org/trainersdirectory/#1519165942001-1b945814-22d7.

Africa Lead has invested in building the capacity of experienced trainers/facilitators that are able to understand and facilitate discussions relating to agricultural transformation and have a proven track record in delivering capacity building training programs for multiple stakeholders within the agricultural sector. https://www.africaleadftf.org/trainersdirectory/#1519165942001-1b945814-22d7.

Africa Lead Program Review (2013-2017)

Between April and June 2017, Africa Lead conducted an internal Program Review which engaged a total of 153 individuals, representing 83 organizations, through a total of 64 interviews in nine countries across 10 national and regional programs. Additional detail on the local context and country or region-specific findings and conclusions, can be found in accompanying material. https://www.africaleadftf.org/knowledge-base/africa-lead-program-review-2013-2017-cross-cutting-conclusions/.

Article: The Hard and Soft Facts of Facilitative Leadership

This blog describes the importance of facilitative leadership and examines the research on the critical role it plays in multi-stakeholder initiatives. https://www.africaleadftf.org/2019/07/31/facilitative-leadership-the-cornerstone-of-multi-stakeholder-collaboration/.

This blog describes the importance of facilitative leadership and examines the research on the critical role it plays in multi-stakeholder initiatives. https://www.africaleadftf.org/2019/07/31/facilitative-leadership-the-cornerstone-of-multi-stakeholder-collaboration/.

Video: Agriculture Council of Kenya

As part of Africa Lead’s continental focus on supporting NSAs’ engagement in agricultural policy dialogue, the program provided support to the Agricultural Council of Kenya to strengthen its organizational development. This learning product depicts the organization’s journey. https://www.africaleadftf.org/2018/08/27/kenyas-agriculture-sector-finds-its-unified-voice/.

Africa Lead sought to develop and strengthen the multi-sectoral, multi-stakeholder collaborative networks, practices, and platforms that make collaborative action possible. These mechanisms help build strong linkages among policy system actors and institutions, as well as streamline communication, facilitate the mobilization of resources, and engender broad stakeholder support for policy priorities, including among groups like women and youth often excluded from policy conversations. By giving stakeholders opportunities to work together successfully, they also build the trust to sustain collaboration and improve policy coherence.

Africa Lead’s work in this program area focused on the following:

Types of Organizations & Support Provided to Africa Lead’s Key Partners (2014 – 2019)

CONTINENTAL

CAADP Non-State Actors Coalition (CNC)

To broaden stakeholder participation in CAADP processes, Africa Lead supported NSAs to launch and strengthen the capacity of the CNC, an inclusive platform for discussing and advocating policies to increase agricultural productivity and enhance food security. Through a grant to the Agency for Cooperation and Research in Development (ACORD), Africa Lead supported the organizational development of the CNC Secretariat. The project also raised CNC’s profile among key CAADP actors, including the African Union Commission, the Regional Economic Communities, and the African Union Development Agency’s New Partnership for Africa’s Development (AUDA-NEPAD). Today, the CNC represents more than 250 affiliate NSAs that serve as a collective voice on CAADP with the African Union, regional bodies, and country leaders.

GHANA

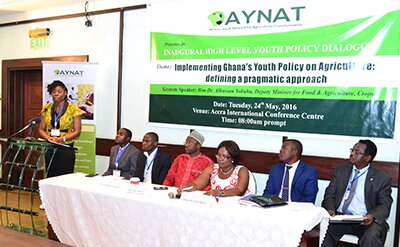

African Youth Network for Agricultural Transformation (AYNAT)

AYNAT aims to “build a network of youth in agriculture who are empowered to lead change toward achieving food security, sustained economic growth, and agricultural transformation in Africa.” Africa Lead supported AYNAT with training, including the Champions for Change leadership course and public policy advocacy and engagement training. AYNAT’s leaders have put their new skills and knowledge into practice, organizing a youth dialogue program to exert pressure on the government to update Ghana’s youth in agriculture policy, improve inclusive consultation with the public, and provide regular updates on its plans.

A key aspect of building sustainable and effective networks and platforms is ensuring they are inclusive and representative of a diverse set of stakeholders. Broad participation in collaborative networks allows stakeholders to interact with one another and engage the government with evidence-based positions on existing and potential policies. As such, Africa Lead mobilized policy actors, participants, and advocates—such as NSAs, the private sector, women, and youth—to participate more fully in agricultural sector decision-making processes. To mobilize stakeholders, the project used grants, capacity building, training, and media and outreach. As a result, more stakeholders—from sectoral associations to farmer groups to young agricultural entrepreneurs—are participating in CAADP processes, and their perspectives are increasingly integral to policy making.

Africa Lead’s work in this program area focused on the following:

KENYA & SENEGAL

NSA Small Grants Program

To strengthen the network of NSAs working in agriculture and on food security, Africa Lead and the CNC launched the NSA Small Grants Program. Grants were designed to improve citizen engagement in food security at the subnational and national levels in Kenya and Senegal. In Kenya, for example, Africa Lead issued a grant to the Open Institute to train farmers and households in Nakuru County to collect and use agricultural data to develop evidence-based policy recommendations. Some 4,000 households contributed data that the Nakuru government has used to prioritize budget allocations for agricultural projects. Africa Lead also facilitated a two-day learning event in Nairobi, where grantees shared lessons learned, and developed a comprehensive learning brief and a video to highlight tools developed through NSA engagement with CAADP processes at the sub-national level.

WEST AFRICA

West African Regional Mango Alliance (WARMA)

In 2016, the Senegalese Ministry of Trade, USAID Senegal, and Africa Lead co-organized West Africa Regional Mango Week, the first-ever platform for stakeholders involved in the regional mango value chain. This platform allowed for a dialogue on critical issues such as access to markets, competitiveness, regulation, and capacity building needs. Following an Africa Lead study on developing a representative body, in September 2017 the WARMA was established. At the first Constituent General Assembly of the WARMA in September 2018, the eight member countries (Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, the Republic of Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, and Senegal) validated WARMA’s constitutional rules and procedures, elected the permanent executive board, and developed a roadmap of priority actions.

TANZANIA, EAST AFRICA

Kumekucha (“It’s a new day” in Kiswahili) and Don’t Lose the Plot, Tanzania, East Africa

In partnership with USAID Tanzania and USAID East Africa separately, Africa Lead developed two innovative media campaigns to engage youth and women in agriculture advocacy and agribusiness. In Tanzania, Africa Lead supported an educational media campaign that entailed a 52-week radio show and a feature length film series, “Kumekucha,” which showed inspiring stories of youth and women smallholder farmers. Africa Lead also supported Africa’s first agriculture reality TV show, “Don’t Lose the Plot,” with youth competing to build the most effective agribusiness. The program was shown across East Africa (Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda). Together, the programming reached nine-plus million women and youth listeners and viewers in Kenya and Tanzania. Kumekucha films and actors have been nominated for and won multiple African film awards, including prizes at the Zanzibar Film Festival.

Policy Reform for Investment Mobilization (PR4I)

Africa Lead established PR4I to support value chain-related policy improvements through small grants to private organizations in Kenya, Senegal, and Tanzania. Multi-stakeholder advisory committees were established in each country to review grant applications and recommend finalist grantees. Among the selected grantees was the Agricultural Council of Tanzania (ACT), which used its grant to identify policy constraints across three value chains. ACT’s analysis showed lack of land registration and the resulting inability to meet collateral requirements for financing to be a constraint across all value chains. It is now equipped with the information it needs to better advocate policy reforms on behalf of value chain participants.

This network map provides a sense of the scale and distribution of institutions supported by Africa Lead through food security events over the entire life of the project, from 2014 to 2019. Each of the small circular elements represents a single institution supported by Africa Lead. These are connected to square elements representing a food security event hosted by Africa Lead. The larger circular elements represent Africa Lead’s buy-ins, these are connected to the food security events they supported and sized by the number of institutions they supported through these events. At the bottom of the map you’ll find a timeline from 2014 to 2019. Selecting and deselecting each year will add or remove the related data points so you can explore the progression of institutions supported by Africa Lead over the life of the project.